Hospital San Juan de Dios

Founded in 1552 by Antón Martín

Inside, there were incurable patients, the contagious, the poorest, those also called ‘the sore skins’. That is, since its creation, the San Juan de Dios Hospital was destined to cure venereal and dermatological diseases.

The promoter and alma mater of the project was Antón Martín, disciple of Juan de Dios and member of his Congregation. The institution was located between calle Atocha and the square that takes the name of his founder.

At the beginning, the San Juan de Dios Hospital had about 20 beds. Little by little it grew, becoming, from 1587, the largest in the town by absorbing Campo del Rey Hospital and San Lázaro Hospital.

For more than three centuries, the hospital fulfilled its mission. In just over half a century, from 1700 to 1757, the number of people attended to was 70,708, including the sick and foundlings. All this, despite the stench emitted by the building, the treatment of prostitutes, the image of the mourners or the complaints of the neighbors.

The old hospital mansion always had an inevitable aura of mystery and legend. Due, on the one hand, to the taboo that prostitution inspired and, on the other, to the rigid Victorian morality that already, in the 19th century, permeated that era.

The famous writer and novelist Pío Baroja in his novel The Tree of Knowledge describes this same Hospital in the following way:

“This hospital, now fortunately pulled down, was a disgusting, dirty, evil-smelling place. Its windows looked onto the Calle de Atocha, and besides their iron bars had a wire netting, so that the sight of the women at the window should not offend the neighborhood. Sun and air were thus excluded.”

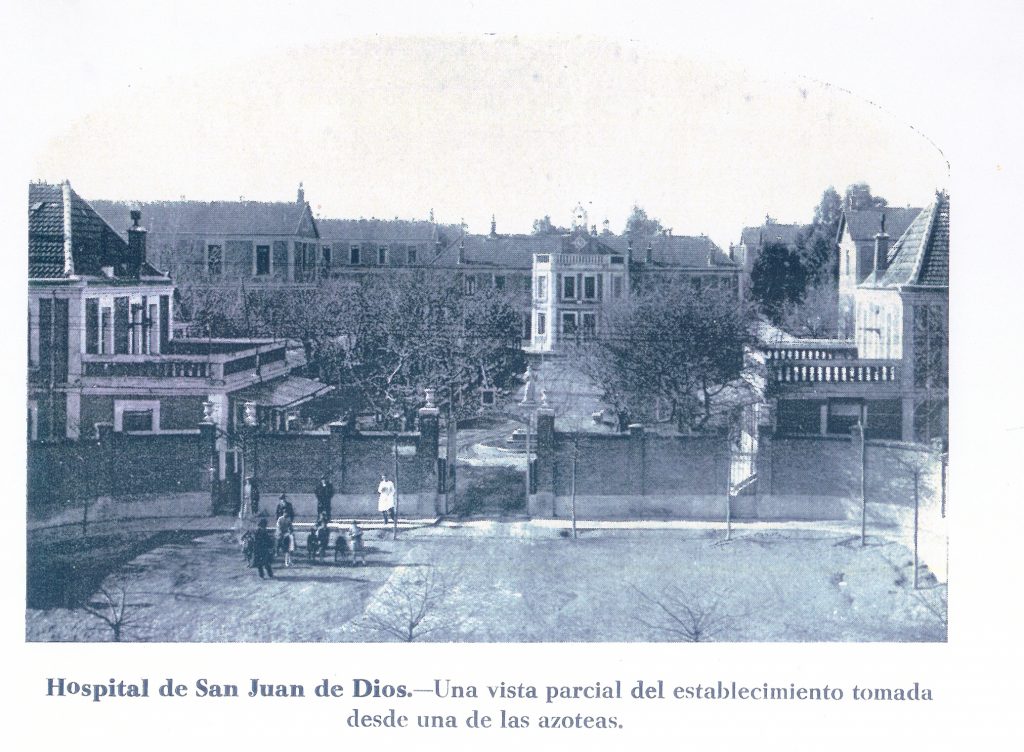

At the end of the 19th century, the hospital building was already very old and saturated. This, together with the fact that the growing urban planning of the time did not view favorably the location of a hospital dedicated to the treatment of venereal diseases in an already central area of Madrid. This led the Provincial Council to build a new building on the outskirts of Madrid located on calle Doctor Esquerdo.

On September 21st, 1897, the transfer to the new establishment took place, formed by a curious procession made up of carts that transported the sick accompanied by the songs and laughter of prostitutes who, as in a bad dream, they left behind the gloomy rooms with bars and lattices of the old establishment, which at times seemed more like a prison than a hospital.

When the new building was inaugurated, it had eight pavilions, with capacity for 850 beds. In addition, there was an oratory, pharmacy laboratory, morgue, chapel, school, laundry and drying room, and correctional cells.

There was also, from the previous hospital, a museum dedicated to reproducing in wax, diseases whose scientific interest was relevant. Its creator was the illustrious dermatologist José Eugenio Olavide, which is why the museum was named in his honor after his death in 1901.

The arrival of salvarsans and bismuth and later the widespread use of penicillin for the treatment of syphilis in the mid-20th century gradually emptied the hospital. The public health reform, together with the need to relocate the old hospital centers of the Provincial Council, condemned it to closure. The now decaying San Juan de Dios Hospital was already quite integrated into the urban structure of the city, as a consequence of the great demographic development of the capital during the fifties and sixties of the last century, together with the improvement of communications.

The San Juan de Dios Hospital probably closed its doors at the end of 1966, thus bringing to an end the main dermatological and venereological reference of Spain for more than 400 years. Some of its facilities and land were reused to become part of the Ciudad Sanitaria Provincial Francisco Franco (the current Gregorio Marañón University General Hospital).

His heritage, and his legacy, continues to this day, thanks among other things to the rescue of this impressive and unusual collection.

"The country, the society, the city itself produced loafers, thugs, pickpockets, prostitutes, helpless men, starving children, in an uncontrolled manner. Neither the charity of the Casa de la Doctrina, nor the workers' organizations which were still small, or any kind of charitable or humanitarian association could remedy or alleviate so much helplessness."

The search. Pio Baroja