History of the Olavide Museum

A jewel in the history of Medicine in Spain

Hidden in Pavilion 8 of the Faculty of Medicine at the Complutense University of Madrid, there can be found an unexpected and unknown jewel from the history of Spanish Medicine: the Olavide Museum, named in honor of the founder and pioneer of Dermatology in our country, Dr. José Eugenio Olavide y Landazábal.

In its main collection of dermatological ceroplastics, all known skin diseases of the time are represented, at a time when color photography was not well developed and these educational artifacts, created directly from patients, served to teach the new generations of doctors.

This is an important collection of wax models made in the 19th and early 20th centuries, based on patients with dermatological conditions. In addition, most of the figures have the original medical records attached to the back of the pieces, which provide incredible medical-historical value.

After the opening of the entire collection, in 2014, a total of 670 works were verified. A collection that together with the plaster molds, sculptures, drawings, lithographic plates and dermatological documentation, constitute the Olavide Museum.

The museum was inaugurated in 1882 under the name of the Museo Anatomo-patológico Cromo-litográfico y Microscópico del Hospital San Juan de Dios.

From that moment on, its history, full of difficulties, concluded with its closure and disappearance between 1966 and 196, a period in which the hospital on calle Doctor Esquerdo, where it had been located since 1897, was demolished.

The international recognition of the museum occurred in 1889, when 90 figures made by the sculptor Enrique Zofío, were transferred to Paris to be exhibited at the 1st International Congress of Dermatology.

The figures were praised by great personalities, highlighting their color according to the profession or the type of illness, which contrasted with the almost uniform tint of the then great Parisian wax sculptor Jules Baretta. At that time, the ceroplastics of San Juan de Dios became known across Europe, and together with the Saint-Louis Museum in Paris, they constituted a world reference.

Years later, in 1919, during the International Medical Exhibition, part of the moulage collection was exhibited at the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid. As an anecdote, it should be noted that the German delegation, which had museums of its own in Dresden and Munich (later destroyed during the Second World War), offered to pay the amount of 30 million pesetas for the exhibited moulages.

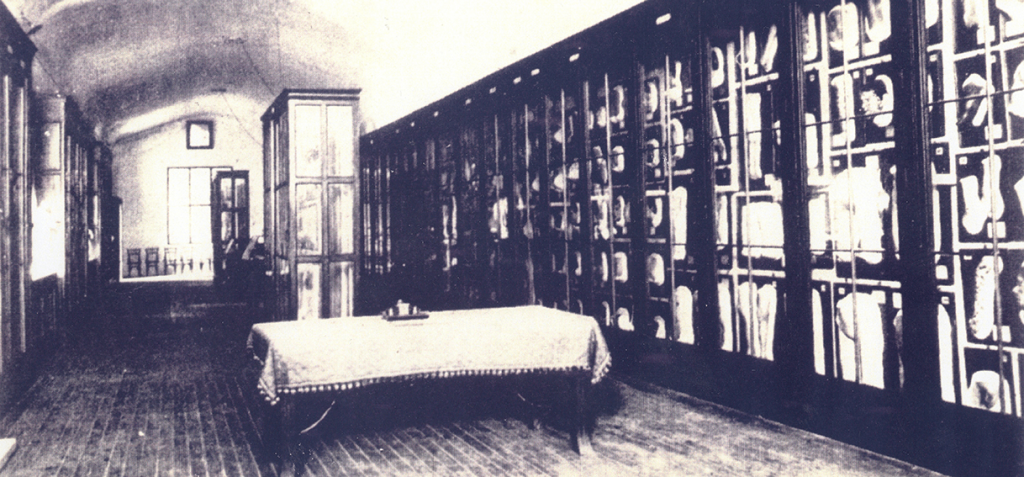

The figures, in their permanent location, were kept in a gallery-type room at the San Juan de Dios Hospital, and were exhibited in large glass cases from the floor to the ceiling in a very similar way to the Saint-Louis Museum in Paris.

Upon the death of José Eugenio Olavide in 1901, the museum was renamed ‘The Olavide Museum’, the name by which it is known today.

During the Spanish Civil War, the museum was visited by hundreds of recruits so that they could see, in a direct and visual way, the horrors of syphilis and other venereal diseases and thus instruct the soldiers in an unambiguous way with the aim of maintaining chastity and morality, but above all, to avoid the contagion and spread of sexually transmitted infections.

Not only militiamen visited the museum, after the sad conflict, but business groups, high school students and medical students also visited its display cases.

All terrified, moved or surprised, but always interested.

Little by little, its popularity declined, opening only on Sundays and greatly limiting its audience. The heavy obscurantism of national-Catholicism did the rest. The Museum was packed up and closed one morning between the years 1966-67 without Don Rafael López Álvarez, its last director, being able to do anything to prevent it.

With the collection stored, it started to be forgotten.

There were many dermatologists who for years tried to recover the entire collection, especially Professor Antonio García Pérez.

Upon his death, Dr. Conde-Salazar in 2005, with the help of restorers Amaya Maruri and David Aranda, and after multiple investigations, recovered the 120 drawers found in warehouses at the Niño Jesús Hospital in Madrid, thanks to the invaluable collaboration of Dr. Antonio Torrelo.

These warehouses were going to be demolished for a hospital renovation.

With this discovery, the appearance of the majority of the Olavide Museum’s collection was completed and the arduous task of restoration, cataloging and enhancement of the old collection began. Thus recovering treasure, which had been abandoned for decades, and was patiently awaiting rediscovery.

A ‘rescue’ of historical-medical heritage launched by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology for lovers of our history, science and art to reconnect.